The conceptual evolution of green building is reflected in historical versions of green building rating tools. Computational text analysis on historical versions of LEED revealed changes in the category systems and textual contents, which reflects how LEED’s green building concept has evolved in the 21st century.

Keywords: green building rating tool (GBRT); conceptual evolution; LEED; computational text analysis

1. Introduction

The concept of green building is constantly evolving ever since Paul Soleri first proposed the idea of “ecological architecture” back in the 1960s [^Chen & Zhao, 2019]. The green building concept have been brought up by various stakeholders, with significant epochal characteristics. The oil crisis back in 1970s triggered a boom in interests in energy-efficient buildings (Wolfson, 2013); health issues like Sick Building Syndrome [^Kibert, 2004) and the COVID-19 pandemic (Ascione et al., 2022) strengthened the importance of occupant health in the green building concept; an interest in resource conservation reemerged in the early 1990s as a consequence of a complex array of effects, e.g., the UN Conference on Sustainable Development in 1992, known as the Rio Conference (Kibert, 2004)… The current definition of green building, provided by World Green Building Council (n.d.), embodies various aspects from environmental impacts to living quality.

Various green building rating systems (GBRTs) have been proposed worldwide as a way to encourage and standardize green building designs and constructions. GBRT usually has an authoritative background (Table 1) and represents the country’s official understanding of green buildings. Through official certifications, they provide important legitimacy for “greenness” of buildings, thus shaping the green building concept conversely (He et al., 2018). In conclusion, the green building concept is deeply intertwined with GBRTs.

Table 1. Authoritative backgrounds of several GBRTs.

| GBRTs | Country | Organization |

|---|---|---|

| LEED | United States | U.S. Green Building Council |

| BREEAM | U.K. | Building Research Establishment |

| Green Star | Australia | Green Building Council of Australia |

| CASBEE | Japan | Japan Sustainable Building Consortium |

Among world’s leading GBRTs, LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) is the most popular (Doan et al., 2017) with 156,914 projects over more than 170 countries/regions1. LEED is also the mostly investigated in current scientific literature (Ascione et al., 2022). Therefore, it can be used as a typical GBRT that reflects the green building concept both in the global industry and academia.

GBRTs have been updated continuously to always meet the newest demand for green building certification. This process provides a potential aspect to explore the conceptual evolution of green buildings. Since the first launch (LEED v1.0 polit) in 1998, LEED has released several new versions from v2.0 in 2001 to the latest v4.1 in 2019. This updating process provides a window for studying conceptual evolution of green building in the 21st century.

Computational text analysis (CTA) refers to harness of computational techniques to analyze big (textual) data (Schaffer Library, 2022), which is suitable for analyzing the large texts in historical versions of LEED rating systems. This paper adopts term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) and cosine similarity for text analysis.

2. Material and methods

2.1.Historical LEED rating materials

The U.S. Green Building Council offers free access to documents of historical versions2. Considering the integrity and continuity of textual data, a series of documents was selected as research objects (Table 2). Ever since version 2.1, LEED has been providing rating systems for different building types and building phases including new construction, interior fit outs, operations and maintenance and core and shell. The list of rating types has changed several times. To focus on the general green building concept, and to maintain consistency and coherence of textual data, only rating systems for general new constructions (NC) were taken into account.

Table 2. Selected historical versions of LEED rating system

| Version | Launch Year | Selected Rating System Title |

|---|---|---|

| v2.0 | 2001 | LEED Rating System Version 2.0 |

| v2.1 | 2002 | LEED Green Building Rating System for New Construction & Major Renovations (LEED-NC) Version 2.1 |

| v2.2 | 2005 | LEED for New Construction & Major Renovations Version 2.2 |

| v3 2009 | 2009 | LEED 2009 for New Construction and Major Renovations |

| v4.0 | 2013 | LEED v4 for Building Design and Construction (BD+C): New Construction |

| v4.1 | 2019 | LEED v4.1 – Building Design and Construction (BD+C): New Construction |

Every rating system was divided into credits according to independent descriptions3 in the document. Total points, credit names, IDs and contents were recorded. To eliminate the interference of text structures, structure-relevant contents (section names like “Intent”, “Requirements”, …) were removed from textual data.

2.2.Computational text analysis

Term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) reflects how important a word is to a document in a collection or corpus. The TF-IDF value of word $\cal {w}\in W$ in document $i$ is defined as

$$ {\rm TFIDF}_{w,i}=\frac{L_{w,i}}{L_{all, i}}\cdot\log\left(\frac{N_{all}}{N_w}+1\right), $$

where $L_{w,i}$ is the number of $w$ word in $i$ document, $L_{all,i}$ is the total amount of words in $i$, $N_{all}$ is the amount of all documents in the collection, and $N_w$ is the number of documents containing $w$. A TF-IDF vector, ${\boldsymbol A}^i\in R^{|{\cal W}|\times1}$, was generated for each document, which refers to an independent credit in this paper.

Cosine similarity was used to quantify the similarity between independent credits from adjacent versions. The connection of ${\boldsymbol A}_{j_1, t}$ credit from $t$ version and ${\boldsymbol A}_{j_2, t’}$ credit from $t’$ version is defines as $$ D(j_1, j_2, t, t’)=1-\frac{{\boldsymbol A}_{j_1, t} \cdot {\boldsymbol A}_{j_2, t’}}{|{\boldsymbol A}_{j_1, t}| \times |{\boldsymbol A}_{j_2, t’}|}. $$ The more similar the contents between the two texts, the closer the value of $D$ is to 1.

All computational text analysis was conducted on Python 3.8.3 under Anaconda3 environment. Codes and data can be found at https://github.com/shengdong00/CTA-LEED.

3. Results

3.1.Changes in independent credit categories

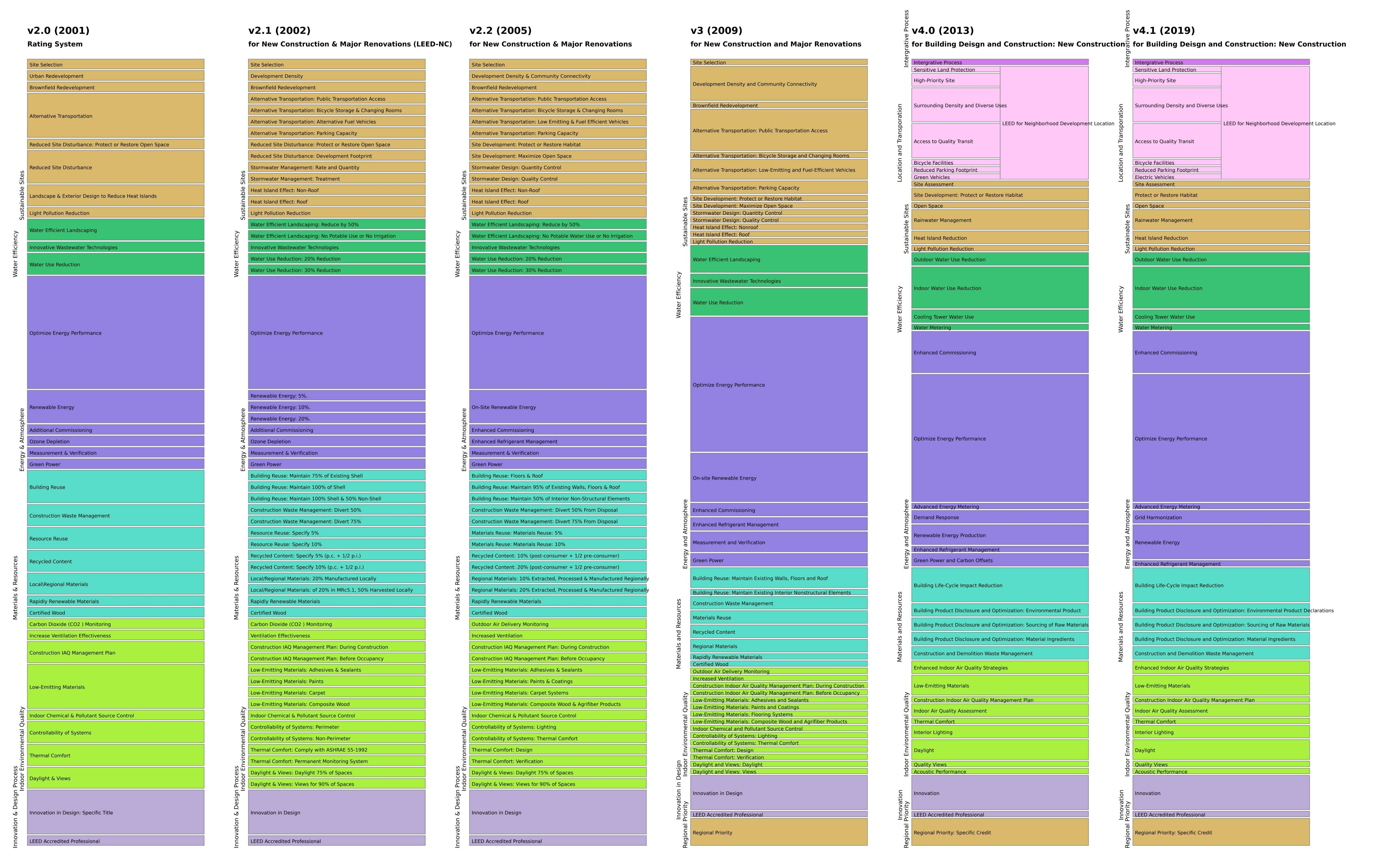

The rating systems have significant changes in categories (Fig 1) after each major update. From v2 to v3, the weights of “Sustainable Sites” and “Energy and Atmosphere” had increased, while that of “Materials and Resources” and “Indoor Environmental Quality” had dropped. From v3 to v4, a series of new categories emerged, including “Integrative Process”, “Location and Transportation”, and “Regional Priority”. Integration and separation of independent credits can be found in each update. E.g., “Low-Emitting Materials” in v2.0 was separated into sub-credits of different usage scenarios in v2.1, and then re-integrated from v3 to v4.0.

Fig 1. Independent credits (with names) of historical LEED versions. Block size stands for the percentage of credit points. Credits of the same category have the same color.

3.2.Content connections

3.2.1 Transition matrices and connection threshold

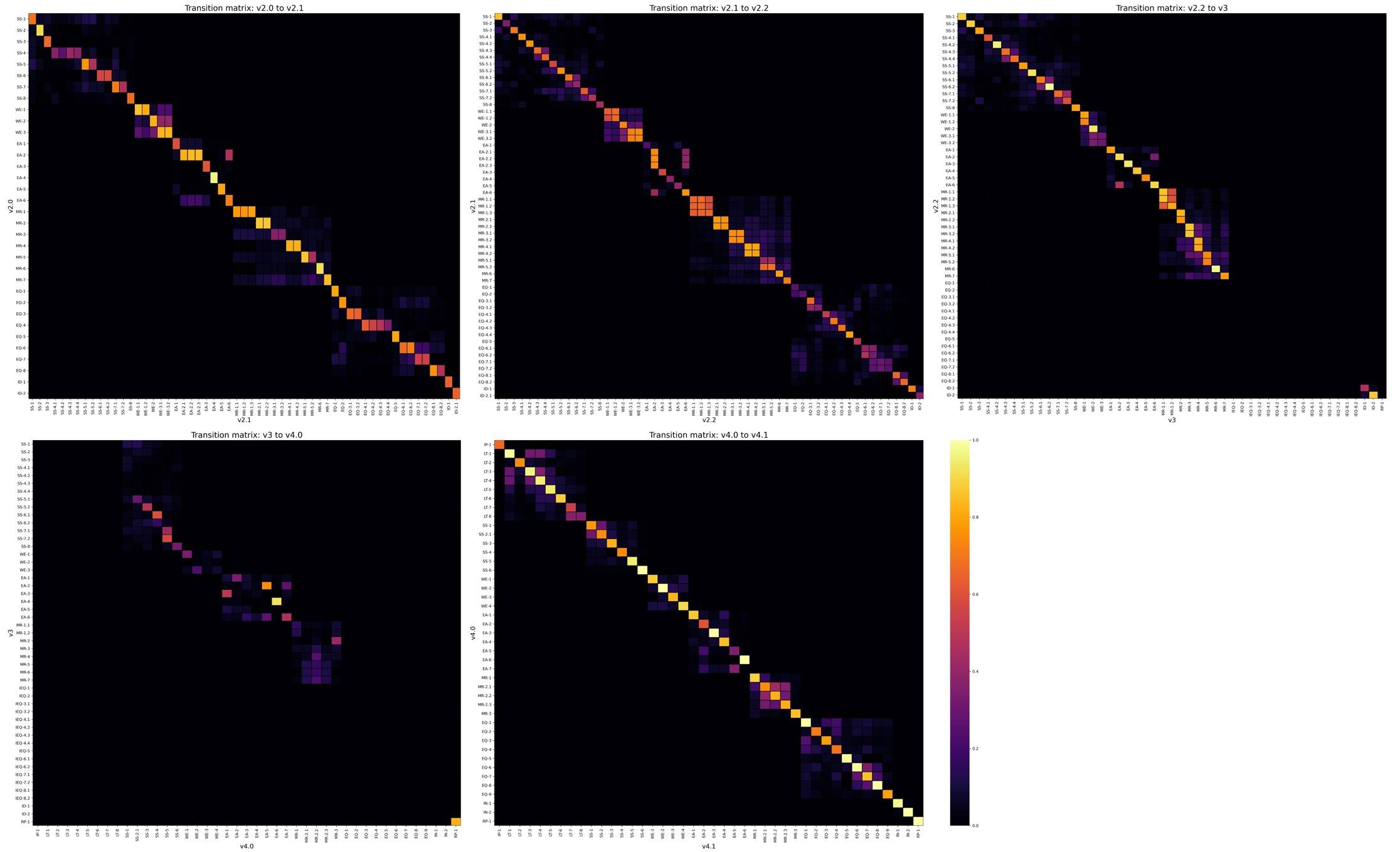

The transition matrices of adjacent LEED versions are created according to the cosine similarities of every two credits (Fig 2). Ideally, a comprehensive, well-classified rating system should divide different aspects of an object into different parts (in this case, credits and categories), and keep its various sub-sections as independent as possible. This is to avoid overlapping of multiple rating processes. Therefore, if a rating system is good and consistent, its credits from a previous version should always be most similar to the corresponding credit in the latter version, with some weaker connections to nearby credits from the same category, and have little connection to credits from a completely different category. This principle is reflected especially in the latest update from v4.0 to v4.1, but not so well-reflected in updates from v2.2 to v3 and from v3 to v4.0. Categories such as environmental quality-related category showed significant change in the 2009 version, and almost everything changed from v3 2009 to v4.0.

Fig 2. Transition matrices of credit connection strengths between adjacent LEED rating systems.

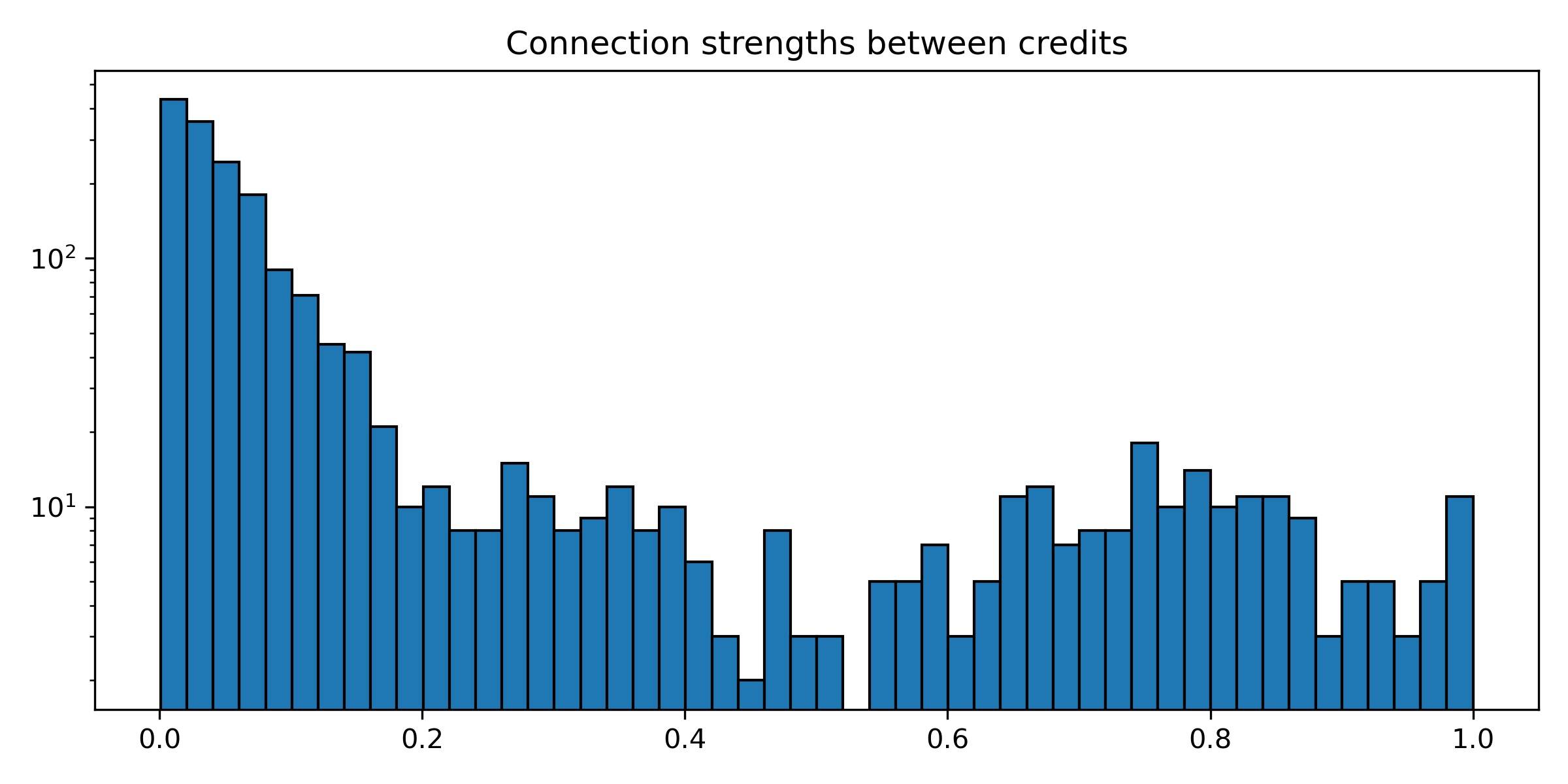

I counted up all the connections and get the histogram in Fig 3. The number of connections dropped drastically from 0.0 to 0.2, and remained at ~101 per bucket(0.02) afterwards. To make the network simple and only illustrates important connections, I used 0.54 as the threshold above which the connections will be considered as significant and marked in Fig 4.

Fig 3. Histogram of connections strengths between credits from adjacent versions.

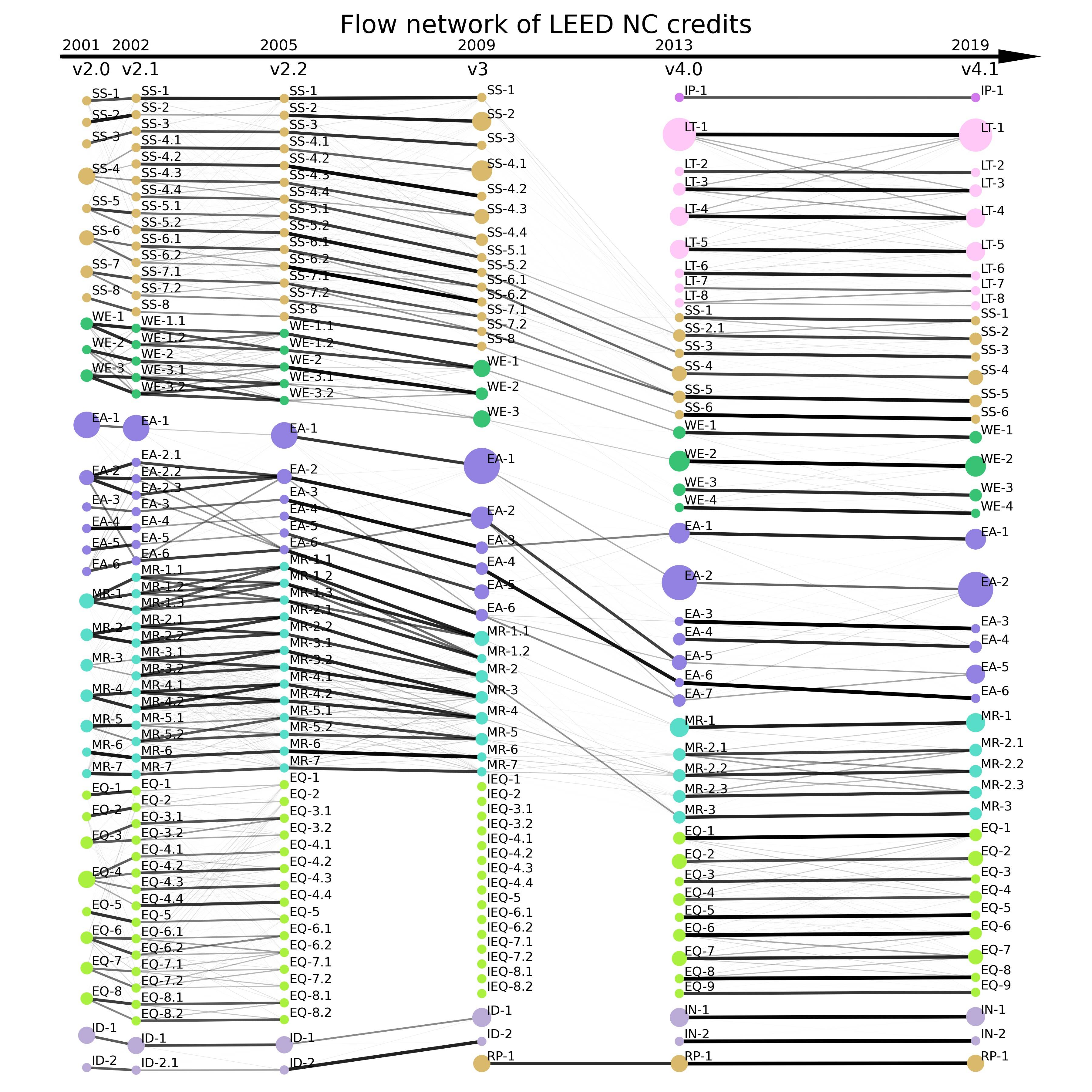

3.2.2 Flow network

Fig 4 shows the flow network of credit ID4 and connections[^5]. Generally, credits in older versions are more intertwined with relevant ones, while credits in later versions mainly connect to their own adjacent credits of the same topic, which means less overlap between independent credits. The clear classification and distinct arrangement indicate the connotational improvement in green building concept.

Relatively, credits have stronger connection with topic-related adjacent credits, with several exceptions. E.g., v3 EA-1 and v4.0 EA-2 both promotes energy performance, but their similarity is only 0.31, which is caused by technical developments in this area. The integration and separation of credits isn’t restricted to “credit/sub-credit” transformations. For example, EA-5 and EA-7 in v4.0 are both loosely connected to EA-5 in v4.1, indicating that green power and carbon offset concerns were merged into renewable energy credit.

Apart from credit-to-credit relations, Fig 4 also reveals content changes at category level. Credits from SS-1 to SS-4 in v3 showed little connection to v4.0 SS, which means the element of transportation and location were basically removed from “Sustainable Site” category. Despite that v4.0 has a new category of “Transportation and Location”, it has no significant connection to v3 SS-1~4. Key word analysis reveals that instead of vehicle management requirements, v4.0 LT focused more on the buildings’ interactions with surrounding facilities and community.

Fig 4. Flow network of independent credits (with IDs). Line width and color stands for cosine similarity.

4. Discussion

There’s a trend of becoming more systematic and multi-dimensional in the update process of LEED rating system. Compared with previous versions, v4 has the biggest change in both category systems and textual contents. The idea of interactions with surroundings and community gets more important in LEED’s green building concept. The connotation of water efficiency, energy, resource conservation and environmental quality had also changed to a great extent to meet with emerging technologies and social-natural backgrounds.

I’m also personally very curious about the socio-economical backgrounds that drastically changed LEED contents in the 3rd version. It would be very interesting to see how the conceptual evolution of green buildings (as well as other environmental topics) was affected by different aspects of the era. By looking into the history, we have the chance to imagine how we are still blinded by the on-going current of times.

References

- Ascione, F., De Masi, R. F., Mastellone, M., & Vanoli, G. P. (2022). Building rating systems: A novel review about capabilities, current limits and open issues. Sustainable Cities and Society, 76, 103498.

- Chen, Y., & Zhao, D. (2019, October). Research and analysis on the development status and prospect of green building materials and green buildings in the new century. In IOP Conference Series. Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 332, No. 3). IOP Publishing.

- Doan, D. T., Ghaffarianhoseini, A., Naismith, N., Zhang, T., Ghaffarianhoseini, A., & Tookey, J. (2017). A critical comparison of green building rating systems. Building and Environment, 123, 243-260.

- Kibert, C. J. (2004). Green buildings: an overview of progress. Journal of Land Use & Environmental Law, 19(2), 491–502.

- He, Y., Kvan, T., Liu, M., & Li, B. (2018). How green building rating systems affect designing green. Building and Environment, 133, 19-31.

- Schaffer Library. (2022, June 30). Digital Scholarship: Computational text analysis. Schaffer Library LibGuides, Union College. https://libguides.union.edu/digital-scholarship/cta

- Wolfson, M. (2013, July 24). Climate Change and Indoor Air Quality: Lessons from the Energy Crisis of the 1970s. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. Retrieved October 23, 2022, from https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/climate-change-and-indoor-air-qualitylessons-from-the-energy-crisis-of-the-1970s

- World Green Building Council. (n.d.). What is green building? Retrieved October 24, 2022, from https://www.worldgbc.org/what-green-building

-

The numbers were retrieved from the official website of LEED on October 24th, 2022. ↩︎

-

Documents available on U.S. Green Building Council website, retrieved on October 5th, 2022. ↩︎

-

An independent and complete text, including sections like “Intent”, “Requirements”, “Potential Technologies & Strategies”, etc. ↩︎

-

Corresponding ID of credits can be found

/Input_data/LEED_credits.xlsxhere. ↩︎