This is a draft version of course essay from Berkeley Summer Session 2021 (EPS-80).

Introduction

Huge environmental changes in my hometown have taken place for the past two decades of fast economic growth and industrialization, which is seen as a rough miniature of entering the Anthropocene. Using examples from class materials, my own experience and the book Under a White Sky, several key aspects of anthropogenic actions are analyzed briefly, including land use, agriculture, soil remediation and green house gas management. Finally some personal insights and preparations are mentioned.

Main Body

A glimpse of Anthropocene — a localized point of view

While I was going through the class, I kept thinking about what happened to my hometown located in the southeastern part of China. The past two decades had witnessed rapid economic growth, industrialization and urbanization. When I recalled on how the landscapes looked like at the beginning and what it had become, I figured that this process could be seen as a miniature of what we’ve been through while entering the Anthropocene, which was believed to have been for just a century or two1. This miniature might not be accurate enough, because no trans-regional effect was involved in the narrative, and the time period is not long enough to verify the geological traces of anthropogenic impacts. Yet we can still find the relations to what we’ve discussed in class and what I’ve read in the book Under the White Sky.

In the early 2000’s I used to spend time in the tiny farm of my grandparents, probably the size of half a tennis court. They grew common vegetables like Chinese cabbages and green vegetables, and in spring dug bamboo shoots from a bamboo forest next to the farmland. The agricultural methods were rather old-fashioned and manual — they used a small plough to loosen the soil, sowed seeds by hand, and used animal excrement as fertilizers. I still remember playing with a small hoe while the adults were busy hoeing to get rid of annoying weeds (I tried to do weeding by myself, but it turned out that all I could do was digging holes in bare soils). There was almost no sign of industrialization and machinery, and even the fence was built out of bamboo strips and wires tied together. This tiny farm provided us with lots of cooking ingredients, and was abandoned after my grandparents moved from the old house.

More and more factories showed up as the economic developed. What used to be villages and fields has become industrial parks with building materials factories, hardware factories and chemical plants. There’s a trend that has been around before I was born that the children of farmers became workers, managers and businessmen. Many of the plants didn’t have anything like a sewage treatment system or an air cleaner. Harmful substances first polluted the workshops where they were created, then infiltrated into the atmosphere and soils, found their ways into the river that flows through the village. The river quickly changed from crystal-clear green to a turbid yellow. Its ecosystem waned as the number of ducks and egrets reduced to zero. At first dead fish could be seen drifting down the river occasionally, later there was nothing left.

Since fields were occupied by various factories, some farmers decided to reclaim lands from less preferable areas, the riverbanks, for example. Trees and bushes were replaced by vegetables with shallow root systems, which increased the speed of soil loss — without strong roots to hold the soil, it was washed away by the river at a faster pace. Some buildings close to the riverbanks were faced with the threat of ground subsidence. One of the houses along the river even collapsed, and half of its walls and bricks fell into water. Luckily nobody get hurt in that accident.

With the public attention to environmental issues, policies were introduced to control industrial sewage and flue gas. Since around 2015, chemical plants were shut down and moved to industry zones with standardized, strict management. These policies soon had their effect as the river became clear again, with fish and ducks coming back to their habitats. Wetlands once used for development are now under remediation, some have turned out to be wetland parks and urban green lands. Though it seems like some toddler steps forward, at least I think we’re heading on the right direction.

Interacting with nature

The ways we’re interacting with nature have multiple and complex effects. These different interactions always tend to create a tangled situation where problems and solutions are not one to one. In this part I’d like to talk about some topics that really impressed me in class, and explore both the merits and downsides of anthropogenic intervention.

Additionally, there’s a kind of paradox in the phrase “interacting with nature”, since most of us agree that human is part of nature. It is odd to think about the idea that the parts can interact with the whole. So to be rigorous, the expression “nature” should be redefined as “the totality of parts other than humanity”.

Proper land use

Land use is more than planning social productive activities. It’s also about planning anthropogenic impacts on nature. Improper land use brings numerous problems including soil degradation, extinction events and green house gas emission. On the other hand, proper land use has tremendous potential to ameliorate these issues.

One of the reasons why land use has such a huge impact lies in its complex structure. As we’ve learned in class, soil consists of different components including 25% of air, 45% of mineral particles, 25% of water and 5% of organic matter (on average level). Of all the organic matter, 80% of it is humus, 10% plant roots and 10% organisms. This staggered structure shows that soil is the the zone where the biosphere, the hydrosphere, the atmosphere and the lithosphere intersect and interact with each other, and we call it “pedosphere”.2 As a result, any changes in soil functions will affect all the these earth systems at the same time, and different systems are able to connect each other via pedosphere. This particular role of soil indicates that how we deal with our lands will have multiple impacts on various issues like climate change, extinct events, extreme weather, etc.

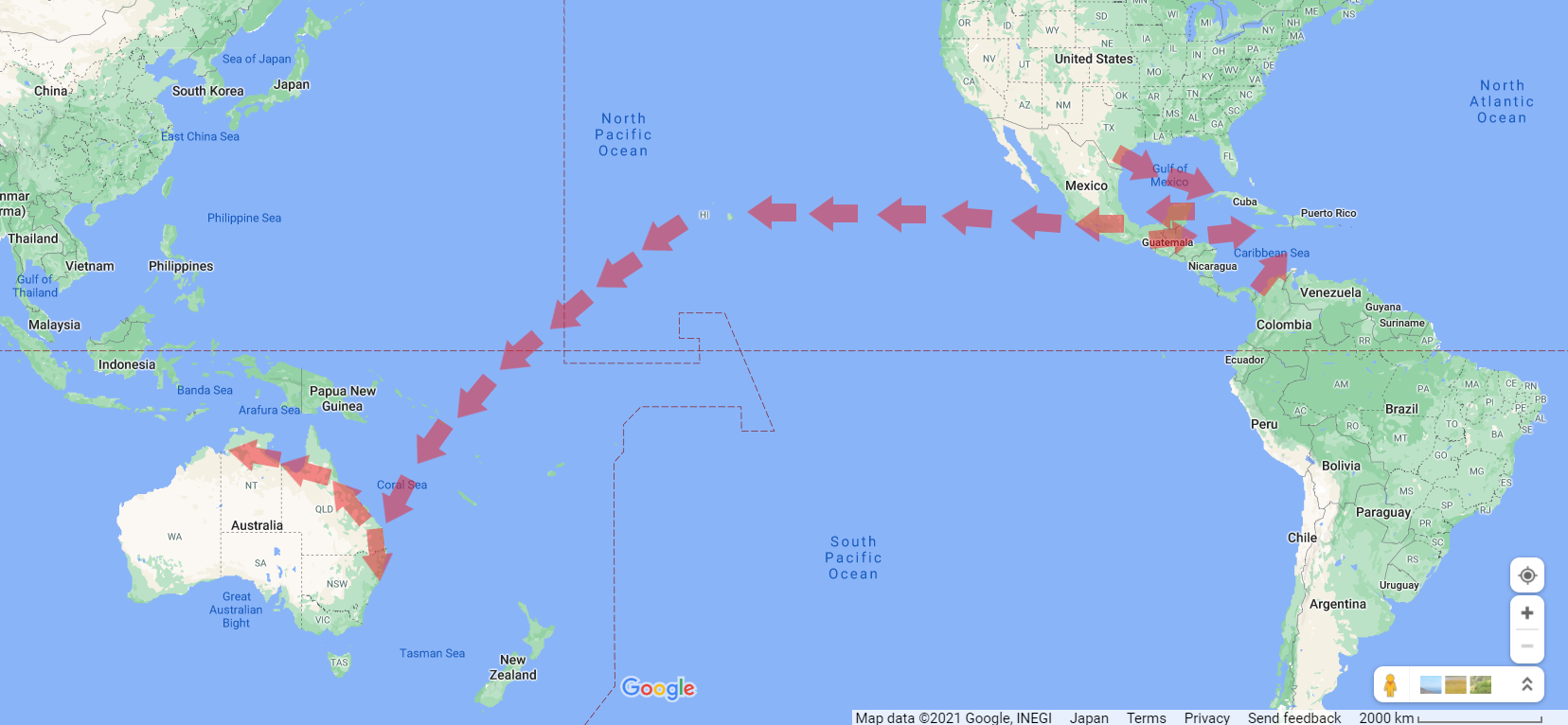

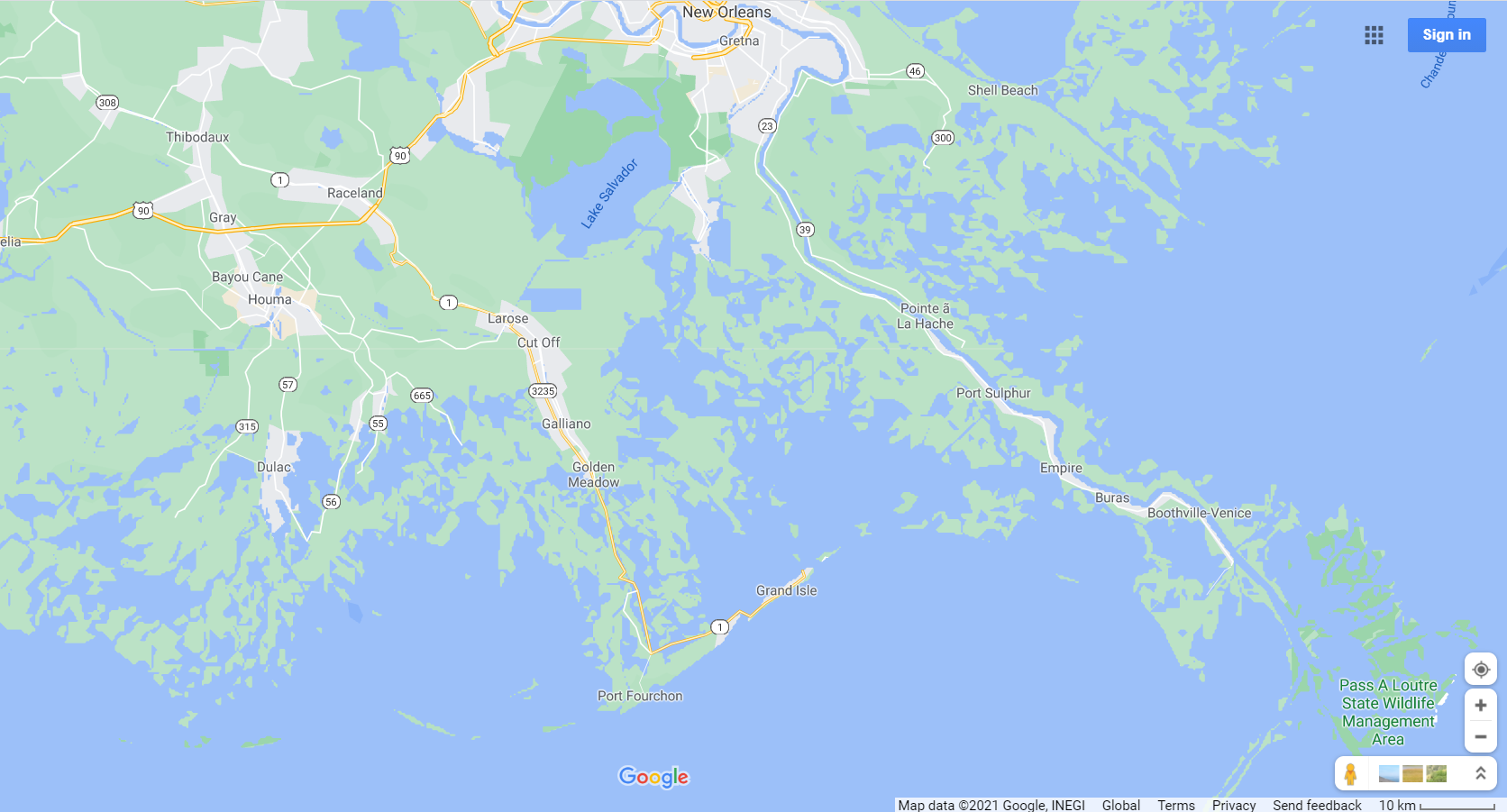

Our casual decisions on land use has led to many crises and threats to both human beings and the natural systems. In Under a White Sky Kolbert talked about a bunch of such lessons. When people tried to grow plants and expand cities in Nevada deserts, the balance of hydrosphere was broken and the water levels in nearby pools began to sink rapidly, and the existence of rare species like the Devils Hole Pupfish was threatened. The land-loss-crisis in New Orleans is also example of obsessive tinkering in which “control is the problem” — the attempts to keep southern Louisiana dry turned out to be the very reason why the Mississippi delta is disintegrating.3 I never went to New Orleans before, but I looked at Google Map and then I realized what it means to be “in tatters”. This reminds me of the little land collapse event near my old home, and warns us the consequence of casual land use and self-righteous tinkering.

I think we don’t know what it exactly means to “solve environmental problems”. In cases like the Mississippi delta, we’re solving environmental problems not for the nature, but for our own benefits. Unexpected results occur when we mistakenly think that we’ve mastered and controlled all the mechanisms in one ecosystem, and that we can use lands for whatever purpose we want. What’s good for human isn’t always good for the ecosystem.

Soil diversity is another things that’s often overlooked in land use planning. As biogeo-chemically dynamic bodies, soil supports terrestrial ecosystems.4 Soil diversity stands for biodiversity to a large extent. Therefore, keeping soil diversity is an important way to control human changes to ecosystems and soil functions.

How we arrange land use indicates our understanding the relationship between human and the earth. A soil that “lives” is what keeps the world rolling. If we neglect the importance of diverse, living soils, we misunderstand our own survival. Before land use planning, consideration should be given to whether the regional soil diversity will be threatened, and whether the soil functions will be maintained. Only after that should we consider how to meet with the social and economical needs.

Agriculture

Agriculture is the part of land use that has a specific impact on soil degradation and green house gas management. Our complete dependence on agriculture makes this issue even more complex. In the US, 6 to 10 times as much land is used for intensive agriculture as for urban areas.5 Food, agriculture and land use counts for 24% of all the green house gas emissions of anthropogenic actions.6

In this class, we’ve been talking about the downsides of industrialized agriculture — how uncovered surface leads to soil nutrient loss, how monoculture lowers biodiversity, etc. Now the curious thing is that if you search “agriculture in US” on the Internet in China, you’ll find many people envy this highly mechanized way of farming. One of the reasons is that China has a shortage of cultivated land, and is in need of higher yields. By 2011, the per capita cultivated land area of China is about 0.083 ha, while that of US is 0.514 ha.7 (As comparison, the average level globally is 0.206 ha per capita.) Secondly, 66% of China’s croplands are located in mountains, hills, and plateaus. Therefore, many of our scientists are engaged in tackling the challenge to mechanize farming and increase output.

But there might be another way out. I realized that regenerative agriculture is more promising in China than I thought. Many of the methods mentioned in class can be found in traditional farming patterns. Take inter-cropping for example, the ancestors have found multiple combinations of crops that would help maintain soil fertility and increase output, like peanuts and cottons, garlic and cabbages, grapes and cucumbers, etc. As I recall my grandparents’ practice in that little farm, I realized that they were conventional experts in regenerative agriculture. With modern technology and knowledges about soils, we can figure out their interactive mechanisms and optimize these summaries of experience.

Turbulence in the biosphere

Biological factor is one of the most powerful among all the elements of earth. Take pedosphere for example, the approximately 5% of organic matter is more than a component that’s passively affected by inorganic environment. Researches have shown that the bio-chemical process of soil microbes influences soil texture such as size of particles. They form a self-organized soil-microbe system, making soil the most diverse ecosystem on the planet.8

Despite the powerfulness of biosphere, it can still be vulnerable when we introduce anthropogenic biological factors. By bringing invasive species, excessive hunting and modern techniques like genetic engineering, we’re using a weapon that’s no less powerful than the natural biosphere.

What we’ve been doing to the biosphere is more like stirring a stick into a still pool, causing turbulence and muddying the water. Once the turbulence is formed, it starts to feed on itself. In the book Under a White Sky, Kolbert mentioned a number of ecosystem disasters caused by human beings carrying species around, including species invasions of Asian carps in Mississippi River and cane toads in Australia.

The story of cane toads is especially dramatic — before these toads conquer the east coast of Australia, it has traveled a long way around the globe. Its story begins when colonists in the Caribbean introduced sugar can from New Guinea as their cash crop. When their cash cows were plagued by beetle grubs, they introduced cane toads from South America and Central America as predators. From there they were shipped to Hawaii and from there to northeast Australia.3 Once they settled down in Australia, they began their horrible march across the continent. People were fooled by the illusion of peace when cane toads invaded the Caribbean and Hawaii, and it was taken for granted that the Australian ecosystem would be able to withstand the cane toads.

There’s a touch of irony in the name “cane toad”, whose official name being “Rhinella marina”. By calling them “cane toads”, we presumed that none of their living habits are really important except that they protect sugar cane. Cane toads were seen as nothing else but a cash-making tool subordinate to sugar cane. This implied an attitude of arrogance which contributed to the disaster in Australia. People find cane toads to be ugly and “hated”. However, it was the error we made that’s truly ugly.

While the power of biology could bring disasters, it can also bring hope to solve some of the biggest ecological challenges, like coral reef bleaching. Scientists studying the Great Barrier Reef were taking attempts to cultivate heat-resistant microbes from the native microbes dwelling in the Great Barrier Reef. By adjusting with the native, we can minimize the risk of bringing disruption to the ecosystem. Assisted evolution and gene drives3 are the main weapons for this mission. However, we still need to be careful not to follow the same old disastrous road of cane toad invasion.

Under a blue sky

The last part of Under a White Sky talked about our role in green house emission and climate change. This part is the highlight of the whole book because climate change is the issue that has been hiding behind most of our topics. We found all the environmental issues — like soil degradation — related to climate change in some way or other. This is also the ultimate issue that links the fates of all human beings and natural systems.

The green house gas we’ve emitted to the atmosphere has been so much that simply cutting down the carbon emission is not enough to stop global warming. Carbon sequestration has become inevitable. Injecting sulfur aerosols into the atmosphere is another proposal which blocks out the electromagnetic radiation heat from the sun. This leads to the title “Under a White Sky”. Kolbert concerned that if someone decided to send out SAILs (Sulfur Aerosol Injection Lofters) into the atmosphere and this plan turned out to be a failure, the result would be a scene of doom to all of us.

I think what Kolbert is trying to say is not that we ought to be freaked out by those terrible possibilities, and simply give up on ourselves. On the contrary, we should be fully aware of the consequences, face the reality, and do the best we can. We have come to a situation with the obligation to help adjust the natural systems. We have learned from history about the terrible consequences of obsessive tinkering. Now we’re dealing with the “ultimate” issue of climate change. In a sense, it feels like the final battle after many encounters.

It is not the earth that we’re fighting for — the blue marble will evolve on its own way regardless of the existence of humanity. Yet there’s only one earth that holds the delicate diversity of lives that we have for now. And there’s one and the only one humanity. When I gets old, I want to tell our next generation with proud, that we’re living in a balanced, regenerative epoch called the Anthropocene.

What to do

This part is some of my personal insights and reflections as a student majoring in environmental science.

Choice of career

I guess part of the reasons that I decided to study environmental science comes from my personal experience — I’ve seen people making vast changes to the landscapes of our hometown, replacing natural lands with industry zones and urban districts, turning waste lands into artificial parks and green belts. Of course I understand that such rapid changes lifted a large population out of poverty, and finally ensured people’s basic needs after centuries of hardship. But I’m still not sure it’s okay for us to design and change the environment, in a seemingly casual manner sometimes.

Decisions of land use are made by the government and land developers, and I can’t make rational comments without detailed information. But having read Under the White Sky, I figure it must be right to keep skeptical and cautious with our interactions with nature. We still don’t know much about the environment surrounding us, and our so-called good deeds often end up being obsessive tinkering. Will these districts, artificial parks and riverbanks become another piece of failed remediation? Will they bring further troubles for the next generation? We have to keep a close eye on that and continue on our search for better, regenerative ways.

Generally speaking, I want to know why we’re in such a situation, and know how to deal with it. I think I’m on the right way to solve these two problems.

Ready for coming crisis

The main challenge of environmental problems will change according to different social-natural conditions. In China, the most concerned topic used to be various pollutions of air and water. But for the coming years I guess we should pay more focus on clean energy, climate change and green city technologies. In many ways, China is about a decade or so behind the US, including urbanization. Therefore, some of America’s environmental concerns might be repeated in China afterwards. Many cities in the US have been big, modern cities for more than a century. However, the general industrialization of many cities in China began only about forty years ago. Contaminated urban soils in these cities may not yet be layered to form a profile, but as time goes by it may well be worth studying. It is important to stay forward-looking and be prepared for possible environmental issues. We’re not supposed to only deal with what is already there.

-

Kolbert, Elizabeth. “Enter the Anthropocene – Age of Man.” National Geographic. 219 (2011): 60-85. ↩︎

-

Lindbo, David, Kozlowski, Deb and Robinson, Clay. Know Soil, Know Life. Madison: Soil Science Society of America, 2012. 1st Edition ↩︎

-

Kolbert, Elizabeth. Under a White Sky. New York: Penguin Random House LLC, 2021. 1st Edition. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Amundson, Ronald, Y. Guo, and P. Gong. “Soil Diversity and Land Use in the United States.” Ecosystems 6.5 (2003): 470-82. ↩︎

-

Pennisi, E. “The Secret Life of Fungi.” Science 304.5677 (2004): 1620-22. ↩︎

-

Primer, A. Drawdown. “Farming Our Way Out of the Climate Crisis.” (2020). ↩︎

-

“Countries Compared by Agriculture > Arable Land > Hectares per Capita. International Statistics.” NationMaster.com, NationMaster. Link. ↩︎

-

Young, I. M. “Interactions and Self-Organization in the Soil-Microbe Complex.” Science 304.5677 (2004): 1634-37. ↩︎